19

May

Parshat Behar: More is Never Enough

This week’s Torah portion speaks of the laws of Shmittah, the Sabbatical year. Every seventh year the Jewish people living in Israel are instructed not to farm, plant or do anything that may improve the land. They must allow their crops to remain uncultivated for the entire year. Furthermore, after the seven Shmittah cycles they are instructed to do the same for the 50th year, the Yovel(Jubilee) year, as they would for the 49th.

Naturally the issue of survival would be paramount on people’s minds and the Torah, anticipating this, offers assurance that it needn’t be an issue. “If you should ask, ‘What will we eat in the seventh year?’ I will ordain My blessing for you in the sixth year and it will yield a crop sufficient for a three-year period.” A bumper crop is promised by God to enable the nation to withstand the year(s) where they cannot farm the land.

Needless to say, these were not easy mitzvot to follow as it required a tremendous sense of trust and faith in God. Indeed the Talmud tells us that people had difficulty “letting go and letting God”, and it is one of the reasons for the Exile after the destruction of the First Temple. Seventy years in fact between the two Temples, to allow the land to reclaim, so to speak, its years of rest from the seventy Shmittah and Yovel years that Israel did not fully comply with.

Shmittah is similar to the mitzvot of the Shabbat and Tzedakah; the common theme being the demand to relinquish our ability and need to conquer and possess. On Shabbat we are told to stop producing, working and creating. Not always an easy request especially in our busy multi-task society where the availability to do stuff is just a click away. Through Tzedakah we are asked to give away a percentage of our earnings to the less fortunate or to institutions that provide spiritual services to our community. In both instances we are instructed to give something up to remind us that, ultimately, our good and welfare is in the hands of God.

By stopping our activities or giving away some of our possessions to others, we learn to overcome the natural tendency to think that what I have gained is solely mine and that my accomplishments are a result of my efforts alone. We come to recognize that, in truth, our achievements are gifts from God – our efforts notwithstanding – as expressed by the phrase, “Man proposes and God disposes”.

The Torah is trying to train us to view our possessions not as a complete free-for-all to do with as we please, but actually on loan from God. Judaism teaches that I am not the sole owner of anything, but a partner with God who also has “rights” to these jointly-owned possessions. This is not an endorsement of Socialism but an awareness that there are two important factors for my success: My total commitment and hard work on the one hand, but also God’s aligning things just the right way to allow me to succeed. Let’s face it, everyone has had times where we put in all the hard work and effort and yet nothing came of it. Ultimately our success is in God’s hands.

Not only do the commandments of Shmittah, Shabbat and Tzedakah help us to recognize that our successes come from God, but they also teach us the important lesson of restraint and how essential that is in our lives. Developing a habit to hold oneself back from obtaining whatever may be within your grasp and capability is a crucial trait for one’s good, welfare and health. Just because it’s there to be had or bought doesn’t mean you ought to go get it.

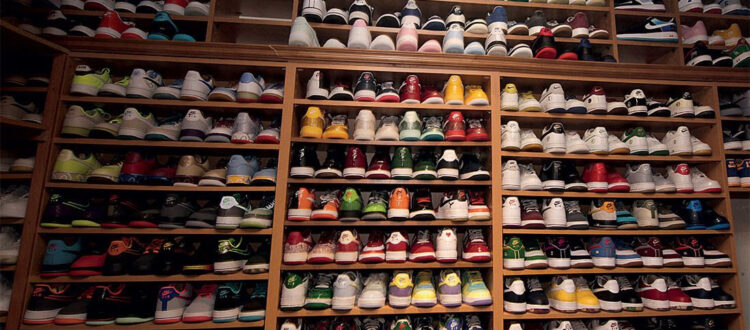

We constantly hear of people who suffer the effects of too much. Too much food, too much work, too much alcohol, too many choices. Homes are not big enough to hold the stuff we own so we rent storage units. We have feelings of inadequacy because the person next to me has more or nicer things and seems to be having a much better time in life according to their Facebook or Instagram posts. The endless consumption goes on and on and it’s never enough since I cannot be happy unless I get the latest, newest, greatest, most chic thing which will provide a moment of fleeting joy. At least until the next latest, newest, greatest, most chic thing comes along to undermine the one I have.

The futility of gathering beyond our needs is poignantly illustrated by a short story by Leo Tolstoy entitled “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” It tells the tale of a man who makes a deal which gives him the opportunity to obtain as much land as he can fully encircle by walking during the course of one day, with the provision that he must make it back to the starting point or he gets nothing.

The man starts out early in the morning, and as he gets further and further out, his eyes catch more and more good land. So he keeps on going. It is only when the day is more than half over that he realizes he’d better make a turn and head back to the beginning, keeping in mind that if he doesn’t fully encircle the land, he ends up with none.

The afternoon wears on and towards the end the man is running. The finish line is in sight as the sun is setting. He tries to run faster but his body is exhausted. Finally, with his last ounce of strength, one moment before sunset, he lunges to the finish line … at which point he collapses and dies.

How much land does a man need? The burial plot was about eight feet.

The Torah tells us, Don’t go astray after the (endless) desires of your heart and your eyes. Don’t end up killing yourself to get even more. It’s never worth it.

Say that you’ll never never never never need it…

All for freedom and for pleasure

Nothing ever lasts forever

Everybody wants to rule the world

-Tears For Fears